This article is about the Indian socialist revolutionary. For the Indian-American civil rights activist, see Bhagat Singh Thind.

"Bhagavath Singh" redirects here. For the 1998 action drama film.

"Bhagavath Singh" redirects here. For the 1998 action drama film.

-

3 people like this

-

0 Posts

-

0 Photos

-

0 Videos

-

History and Facts

Recent Updates

-

Books:

Singh, Bhagat (27 September 1931). Why I Am an Atheist./Singh, Bhagat (2007). Bhagat Singh : ideas on freedom, liberty and revolution : Jail notes of a revolutionary./Singh, Bhagat; Press, General (31 December 2019). Jail Diary and Other Writings/Singh, Bhagat (28 January 2010). Ideas of a Nation: Singh, Bhagat./Singh, Bhagat; Press, General (2 October 2019). No Hanging, Please Shoot Us/.Singh, Bhagat (2020). The Complete Writings of Bhagat Singh : Why I am an Atheist, The Red Pamphlet, Introduction to Dreamland./Singh, Bhagat (2009). Selected works of Bhagat Singh./ Singh, Bhagat (2007). Śahīda Bhagata Siṃha : dastāvejoṃ ke āine meṃ./ Singh, Bhagat (15 August 2019). Letter to my Father./Singh, Bhagat (2008). Bhagatasiṃha ke rājanītika dastāveja./Singh, Bhagat (2010). Bhagat Singh ke siyāsī dastāvez.Books: Singh, Bhagat (27 September 1931). Why I Am an Atheist./Singh, Bhagat (2007). Bhagat Singh : ideas on freedom, liberty and revolution : Jail notes of a revolutionary./Singh, Bhagat; Press, General (31 December 2019). Jail Diary and Other Writings/Singh, Bhagat (28 January 2010). Ideas of a Nation: Singh, Bhagat./Singh, Bhagat; Press, General (2 October 2019). No Hanging, Please Shoot Us/.Singh, Bhagat (2020). The Complete Writings of Bhagat Singh : Why I am an Atheist, The Red Pamphlet, Introduction to Dreamland./Singh, Bhagat (2009). Selected works of Bhagat Singh./ Singh, Bhagat (2007). Śahīda Bhagata Siṃha : dastāvejoṃ ke āine meṃ./ Singh, Bhagat (15 August 2019). Letter to my Father./Singh, Bhagat (2008). Bhagatasiṃha ke rājanītika dastāveja./Singh, Bhagat (2010). Bhagat Singh ke siyāsī dastāvez.0 Comments 0 Shares 0 ReviewsPlease log in to like, share and comment! -

Gandhi controversy:

There have been suggestions that Gandhi had an opportunity to stop Singh's execution but refrained from doing so. Another theory is that Gandhi actively conspired with the British to have Singh executed. In contrast, Gandhi's supporters argue that he did not have enough influence with the British to stop the execution, much less arrange it, but claim that he did his best to save Singh's life. They also assert that Singh's role in the independence movement was no threat to Gandhi's role as its leader, so he would have no reason to want him dead. Gandhi always maintained that he was a great admirer of Singh's patriotism. He also stated that he was opposed to Singh's execution (and for that matter, capital punishment in general) and proclaimed that he had no power to stop it. Of Singh's execution Gandhi said: "The government certainly had the right to hang these men. However, there are some rights which do credit to those who possess them only if they are enjoyed in name only." Gandhi also once remarked about capital punishment: "I cannot in all conscience agree to anyone being sent to the gallows. God alone can take life, because he alone gives it." Gandhi had managed to have 90,000 political prisoners, who were not members of his Satyagraha movement, released under the Gandhi–Irwin Pact. According to a report in the Indian magazine Frontline, he did plead several times for the commutation of the death sentences of Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev, including a personal visit on 19 March 1931. In a letter to the Viceroy on the day of their execution, he pleaded fervently for commutation, not knowing that the letter would arrive too late. Lord Irwin, the Viceroy, later said:

As I listened to Mr. Gandhi putting the case for commutation before me, I reflected first on what significance it surely was that the apostle of non-violence should so earnestly be pleading the cause of the devotees of a creed so fundamentally opposed to his own, but I should regard it as wholly wrong to allow my judgement to be influenced by purely political considerations. I could not imagine a case in which under the law, penalty had been more directly deserved.Gandhi controversy: There have been suggestions that Gandhi had an opportunity to stop Singh's execution but refrained from doing so. Another theory is that Gandhi actively conspired with the British to have Singh executed. In contrast, Gandhi's supporters argue that he did not have enough influence with the British to stop the execution, much less arrange it, but claim that he did his best to save Singh's life. They also assert that Singh's role in the independence movement was no threat to Gandhi's role as its leader, so he would have no reason to want him dead. Gandhi always maintained that he was a great admirer of Singh's patriotism. He also stated that he was opposed to Singh's execution (and for that matter, capital punishment in general) and proclaimed that he had no power to stop it. Of Singh's execution Gandhi said: "The government certainly had the right to hang these men. However, there are some rights which do credit to those who possess them only if they are enjoyed in name only." Gandhi also once remarked about capital punishment: "I cannot in all conscience agree to anyone being sent to the gallows. God alone can take life, because he alone gives it." Gandhi had managed to have 90,000 political prisoners, who were not members of his Satyagraha movement, released under the Gandhi–Irwin Pact. According to a report in the Indian magazine Frontline, he did plead several times for the commutation of the death sentences of Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev, including a personal visit on 19 March 1931. In a letter to the Viceroy on the day of their execution, he pleaded fervently for commutation, not knowing that the letter would arrive too late. Lord Irwin, the Viceroy, later said: As I listened to Mr. Gandhi putting the case for commutation before me, I reflected first on what significance it surely was that the apostle of non-violence should so earnestly be pleading the cause of the devotees of a creed so fundamentally opposed to his own, but I should regard it as wholly wrong to allow my judgement to be influenced by purely political considerations. I could not imagine a case in which under the law, penalty had been more directly deserved.0 Comments 0 Shares 0 Reviews -

Execution:

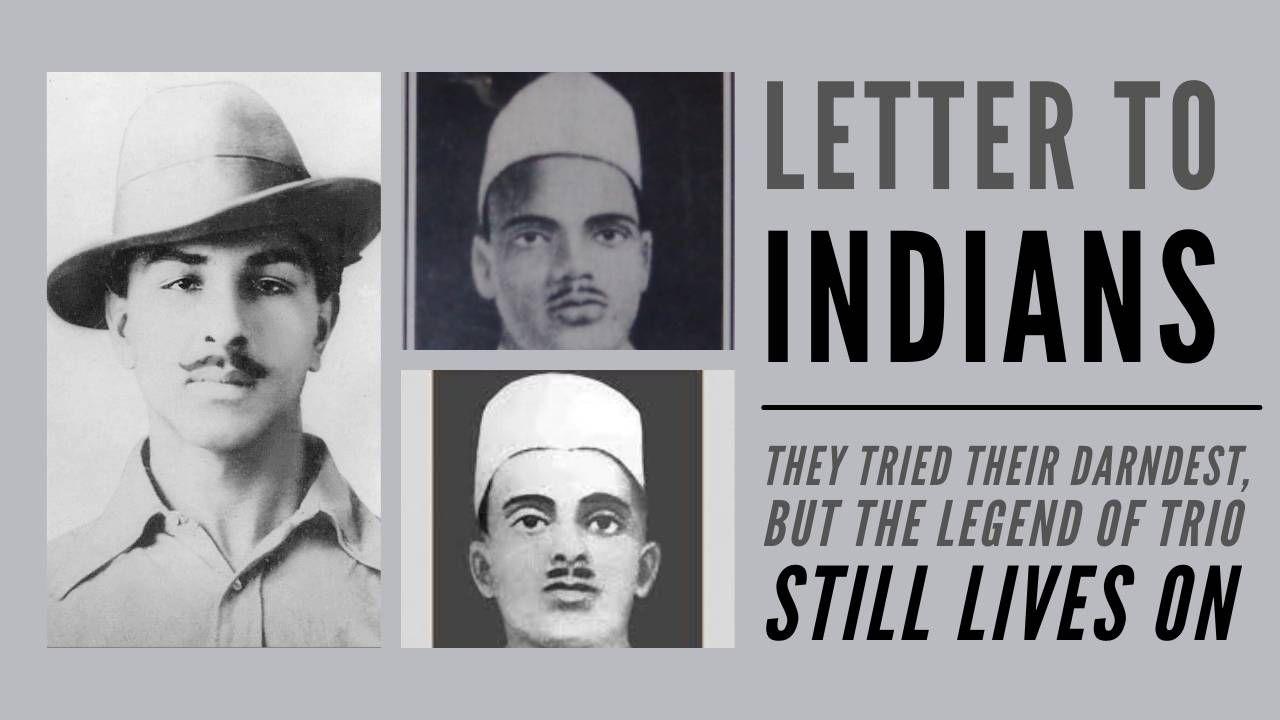

Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were sentenced to death in the Lahore conspiracy case and ordered to be hanged on 24 March 1931. The schedule was moved forward by 11 hours and the three were hanged on 23 March 1931 at 7:30 pm in the Lahore jail. It is reported that no magistrate at the time was willing to supervise Singh's hanging as was required by law. The execution was supervised instead by an honorary judge, who also signed the three death warrants, as their original warrants had expired. The jail authorities then broke a hole in the rear wall of the jail, removed the bodies, and secretly cremated the three men under cover of darkness outside Ganda Singh Wala village, and then threw the ashes into the Sutlej river, about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from Ferozepore.Execution: Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were sentenced to death in the Lahore conspiracy case and ordered to be hanged on 24 March 1931. The schedule was moved forward by 11 hours and the three were hanged on 23 March 1931 at 7:30 pm in the Lahore jail. It is reported that no magistrate at the time was willing to supervise Singh's hanging as was required by law. The execution was supervised instead by an honorary judge, who also signed the three death warrants, as their original warrants had expired. The jail authorities then broke a hole in the rear wall of the jail, removed the bodies, and secretly cremated the three men under cover of darkness outside Ganda Singh Wala village, and then threw the ashes into the Sutlej river, about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from Ferozepore.0 Comments 0 Shares 0 Reviews -

Reactions to the judgement:

After the rejection of the appeal to the Privy Council, Congress party president Madan Mohan Malaviya filed a mercy appeal before Irwin on 14 February 1931. Some prisoners sent Mahatma Gandhi an appeal to intervene. In his notes dated 19 March 1931, the Viceroy recorded:

While returning Gandhiji asked me if he could talk about the case of Bhagat Singh because newspapers had come out with the news of his slated hanging on March 24th. It would be a very unfortunate day because on that day the new president of the Congress had to reach Karachi and there would be a lot of hot discussion. I explained to him that I had given a very careful thought to it but I did not find any basis to convince myself to commute the sentence. It appeared he found my reasoning weighty.

The Communist Party of Great Britain expressed its reaction to the case:

The history of this case, of which we do not come across any example in relation to the political cases, reflects the symptoms of callousness and cruelty which is the outcome of bloated desire of the imperialist government of Britain so that fear can be instilled in the hearts of the repressed people.

A plan to rescue Singh and fellow HSRA inmates from the jail failed. HSRA member Durga Devi's husband, Bhagwati Charan Vohra, attempted to manufacture bombs for the purpose, but died when they exploded accidentally.Reactions to the judgement: After the rejection of the appeal to the Privy Council, Congress party president Madan Mohan Malaviya filed a mercy appeal before Irwin on 14 February 1931. Some prisoners sent Mahatma Gandhi an appeal to intervene. In his notes dated 19 March 1931, the Viceroy recorded: While returning Gandhiji asked me if he could talk about the case of Bhagat Singh because newspapers had come out with the news of his slated hanging on March 24th. It would be a very unfortunate day because on that day the new president of the Congress had to reach Karachi and there would be a lot of hot discussion. I explained to him that I had given a very careful thought to it but I did not find any basis to convince myself to commute the sentence. It appeared he found my reasoning weighty. The Communist Party of Great Britain expressed its reaction to the case: The history of this case, of which we do not come across any example in relation to the political cases, reflects the symptoms of callousness and cruelty which is the outcome of bloated desire of the imperialist government of Britain so that fear can be instilled in the hearts of the repressed people. A plan to rescue Singh and fellow HSRA inmates from the jail failed. HSRA member Durga Devi's husband, Bhagwati Charan Vohra, attempted to manufacture bombs for the purpose, but died when they exploded accidentally.0 Comments 0 Shares 0 Reviews -

Appeal to the Privy Council:

In Punjab province, a defence committee drew up a plan to appeal to the Privy Council. Singh was initially against the appeal but later agreed to it in the hope that the appeal would popularise the HSRA in Britain. The appellants claimed that the ordinance which created the tribunal was invalid while the government countered that the Viceroy was completely empowered to create such a tribunal. The appeal was dismissed by Judge Viscount Dunedin.Appeal to the Privy Council: In Punjab province, a defence committee drew up a plan to appeal to the Privy Council. Singh was initially against the appeal but later agreed to it in the hope that the appeal would popularise the HSRA in Britain. The appellants claimed that the ordinance which created the tribunal was invalid while the government countered that the Viceroy was completely empowered to create such a tribunal. The appeal was dismissed by Judge Viscount Dunedin.0 Comments 0 Shares 0 Reviews -

Special Tribunal:

To speed up the slow trial, the Viceroy, Lord Irwin, declared an emergency on 1 May 1930 and introduced an ordinance to set up a special tribunal composed of three high court judges for the case. This decision cut short the normal process of justice as the only appeal after the tribunal was to the Privy Council located in England.

On 2 July 1930, a habeas corpus petition was filed in the High Court challenging the ordinance on the grounds that it was ultra vires and, therefore, illegal; the Viceroy had no powers to shorten the customary process of determining justice. The petition argued that the Defence of India Act 1915 allowed the Viceroy to introduce an ordinance, and set up such a tribunal, only under conditions of a breakdown of law-and-order, which, it was claimed in this case, had not occurred. However, the petition was dismissed as being premature.

Carden-Noad presented the government's charges of conducting robberies, and the illegal acquisition of arms and ammunition among others. The evidence of G. T. H. Hamilton Harding, the Lahore superintendent of police, shocked the court. He stated that he had filed the first information report against the accused under specific orders from the chief secretary to the governor of Punjab and that he was unaware of the details of the case. The prosecution depended mainly on the evidence of P. N. Ghosh, Hans Raj Vohra, and Jai Gopal who had been Singh's associates in the HSRA. On 10 July 1930, the tribunal decided to press charges against only 15 of the 18 accused and allowed their petitions to be taken up for hearing the next day. The trial ended on 30 September 1930. The three accused, whose charges were withdrawn, included Dutt who had already been given a life sentence in the Assembly bomb case.

The ordinance (and the tribunal) would lapse on 31 October 1930 as it had not been passed by the Central Assembly or the British Parliament. On 7 October 1930, the tribunal delivered its 300-page judgement based on all the evidence and concluded that the participation of Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru in Saunder's murder was proven. They were sentenced to death by hanging. Of the other accused, three were acquitted (Ajoy Ghosh, Jatindra Nath Sanyal and Des Raj), Kundan Lal received seven years' rigorous imprisonment, Prem Dutt received five years of the same, and the remaining seven (Kishori Lal, Mahabir Singh, Bijoy Kumar Sinha, Shiv Verma, Gaya Prasad, Jai Dev and Kamalnath Tewari) were all sentenced to transportation for life.Special Tribunal: To speed up the slow trial, the Viceroy, Lord Irwin, declared an emergency on 1 May 1930 and introduced an ordinance to set up a special tribunal composed of three high court judges for the case. This decision cut short the normal process of justice as the only appeal after the tribunal was to the Privy Council located in England. On 2 July 1930, a habeas corpus petition was filed in the High Court challenging the ordinance on the grounds that it was ultra vires and, therefore, illegal; the Viceroy had no powers to shorten the customary process of determining justice. The petition argued that the Defence of India Act 1915 allowed the Viceroy to introduce an ordinance, and set up such a tribunal, only under conditions of a breakdown of law-and-order, which, it was claimed in this case, had not occurred. However, the petition was dismissed as being premature. Carden-Noad presented the government's charges of conducting robberies, and the illegal acquisition of arms and ammunition among others. The evidence of G. T. H. Hamilton Harding, the Lahore superintendent of police, shocked the court. He stated that he had filed the first information report against the accused under specific orders from the chief secretary to the governor of Punjab and that he was unaware of the details of the case. The prosecution depended mainly on the evidence of P. N. Ghosh, Hans Raj Vohra, and Jai Gopal who had been Singh's associates in the HSRA. On 10 July 1930, the tribunal decided to press charges against only 15 of the 18 accused and allowed their petitions to be taken up for hearing the next day. The trial ended on 30 September 1930. The three accused, whose charges were withdrawn, included Dutt who had already been given a life sentence in the Assembly bomb case. The ordinance (and the tribunal) would lapse on 31 October 1930 as it had not been passed by the Central Assembly or the British Parliament. On 7 October 1930, the tribunal delivered its 300-page judgement based on all the evidence and concluded that the participation of Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru in Saunder's murder was proven. They were sentenced to death by hanging. Of the other accused, three were acquitted (Ajoy Ghosh, Jatindra Nath Sanyal and Des Raj), Kundan Lal received seven years' rigorous imprisonment, Prem Dutt received five years of the same, and the remaining seven (Kishori Lal, Mahabir Singh, Bijoy Kumar Sinha, Shiv Verma, Gaya Prasad, Jai Dev and Kamalnath Tewari) were all sentenced to transportation for life.0 Comments 0 Shares 0 Reviews -

Hunger strike and Lahore conspiracy case:

Singh was re-arrested for murdering Saunders and Chanan Singh based on substantial evidence against him, including statements by his associates, Hans Raj Vohra and Jai Gopal. His life sentence in the Assembly Bomb case was deferred until the Saunders case was decided. He was sent to Central Jail Mianwali from the Delhi jail. There he witnessed discrimination between European and Indian prisoners. He considered himself, along with others, to be a political prisoner. He noted that he had received an enhanced diet at Delhi which was not being provided at Mianwali. He led other Indian, self-identified political prisoners he felt were being treated as common criminals in a hunger strike. They demanded equality in food standards, clothing, toiletries, and other hygienic necessities, as well as access to books and a daily newspaper. They argued that they should not be forced to do manual labour or any undignified work in the jail.

The hunger strike inspired a rise in public support for Singh and his colleagues from around June 1929. The Tribune newspaper was particularly prominent in this movement and reported on mass meetings in places such as Lahore and Amritsar. The government had to apply Section 144 of the criminal code in an attempt to limit gatherings.

Jawaharlal Nehru met Singh and the other strikers in Central Jail Mianwali. After the meeting, he stated:

I was very much pained to see the distress of the heroes. They have staked their lives in this struggle. They want that political prisoners should be treated as political prisoners. I am quite hopeful that their sacrifice would be crowned with success.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah spoke in support of the strikers in the Assembly, saying:

The man who goes on hunger strike has a soul. He is moved by that soul, and he believes in the justice of his cause ... however much you deplore them and, however, much you say they are misguided, it is the system, this damnable system of governance, which is resented by the people.

The government tried to break the strike by placing different food items in the prison cells to test the prisoners' resolve. Water pitchers were filled with milk so that either the prisoners remained thirsty or broke their strike; nobody faltered and the impasse continued. The authorities then attempted force-feeding the prisoners but this was resisted. With the matter still unresolved, the Indian Viceroy, Lord Irwin, cut short his vacation in Simla to discuss the situation with jail authorities. Since the activities of the hunger strikers had gained popularity and attention amongst the people nationwide, the government decided to advance the start of the Saunders murder trial, which was henceforth called the Lahore Conspiracy Case. Singh was transported to Borstal Jail, Lahore, and the trial began there on 10 July 1929. In addition to charging them with the murder of Saunders, Singh and the 27 other prisoners were charged with plotting a conspiracy to murder Scott, and waging a war against the King. Singh, still on hunger strike, had to be carried to the court handcuffed on a stretcher; he had lost 14 pounds (6.4 kg) from his original weight of 133 pounds (60 kg) since beginning the strike.

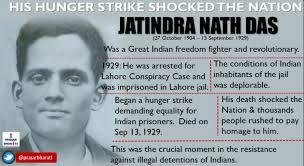

The government was beginning to make concessions but refused to move on the core issue of recognising the classification of "political prisoner". In the eyes of officials, if someone broke the law then that was a personal act, not a political one, and they were common criminals. By now, the condition of another hunger striker, Jatindra Nath Das, lodged in the same jail, had deteriorated considerably. The Jail committee recommended his unconditional release, but the government rejected the suggestion and offered to release him on bail. On 13 September 1929, Das died after a 63-day hunger strike. Almost all the nationalist leaders in the country paid tribute to Das' death. Mohammad Alam and Gopi Chand Bhargava resigned from the Punjab Legislative Council in protest, and Nehru moved a successful adjournment motion in the Central Assembly as a censure against the "inhumane treatment" of the Lahore prisoners. Singh finally heeded a resolution of the Congress party, and a request by his father, ending his hunger strike on 5 October 1929 after 116 days. During this period, Singh's popularity among common Indians extended beyond Punjab.

Singh's attention now turned to his trial, where he was to face a Crown prosecution team comprising C. H. Carden-Noad, Kalandar Ali Khan, Jai Gopal Lal, and the prosecuting inspector, Bakshi Dina Nath. The defence was composed of eight lawyers. Prem Dutt Verma, the youngest amongst the 27 accused, threw his slipper at Gopal when he turned and became a prosecution witness in court. As a result, the magistrate ordered that all the accused should be handcuffed. Singh and others refused to be handcuffed and were subjected to brutal beating. The revolutionaries refused to attend the court and Singh wrote a letter to the magistrate citing various reasons for their refusal. The magistrate ordered the trial to proceed without the accused or members of the HSRA. This was a setback for Singh as he could no longer use the trial as a forum to publicise his views.Hunger strike and Lahore conspiracy case: Singh was re-arrested for murdering Saunders and Chanan Singh based on substantial evidence against him, including statements by his associates, Hans Raj Vohra and Jai Gopal. His life sentence in the Assembly Bomb case was deferred until the Saunders case was decided. He was sent to Central Jail Mianwali from the Delhi jail. There he witnessed discrimination between European and Indian prisoners. He considered himself, along with others, to be a political prisoner. He noted that he had received an enhanced diet at Delhi which was not being provided at Mianwali. He led other Indian, self-identified political prisoners he felt were being treated as common criminals in a hunger strike. They demanded equality in food standards, clothing, toiletries, and other hygienic necessities, as well as access to books and a daily newspaper. They argued that they should not be forced to do manual labour or any undignified work in the jail. The hunger strike inspired a rise in public support for Singh and his colleagues from around June 1929. The Tribune newspaper was particularly prominent in this movement and reported on mass meetings in places such as Lahore and Amritsar. The government had to apply Section 144 of the criminal code in an attempt to limit gatherings. Jawaharlal Nehru met Singh and the other strikers in Central Jail Mianwali. After the meeting, he stated: I was very much pained to see the distress of the heroes. They have staked their lives in this struggle. They want that political prisoners should be treated as political prisoners. I am quite hopeful that their sacrifice would be crowned with success. Muhammad Ali Jinnah spoke in support of the strikers in the Assembly, saying: The man who goes on hunger strike has a soul. He is moved by that soul, and he believes in the justice of his cause ... however much you deplore them and, however, much you say they are misguided, it is the system, this damnable system of governance, which is resented by the people. The government tried to break the strike by placing different food items in the prison cells to test the prisoners' resolve. Water pitchers were filled with milk so that either the prisoners remained thirsty or broke their strike; nobody faltered and the impasse continued. The authorities then attempted force-feeding the prisoners but this was resisted. With the matter still unresolved, the Indian Viceroy, Lord Irwin, cut short his vacation in Simla to discuss the situation with jail authorities. Since the activities of the hunger strikers had gained popularity and attention amongst the people nationwide, the government decided to advance the start of the Saunders murder trial, which was henceforth called the Lahore Conspiracy Case. Singh was transported to Borstal Jail, Lahore, and the trial began there on 10 July 1929. In addition to charging them with the murder of Saunders, Singh and the 27 other prisoners were charged with plotting a conspiracy to murder Scott, and waging a war against the King. Singh, still on hunger strike, had to be carried to the court handcuffed on a stretcher; he had lost 14 pounds (6.4 kg) from his original weight of 133 pounds (60 kg) since beginning the strike. The government was beginning to make concessions but refused to move on the core issue of recognising the classification of "political prisoner". In the eyes of officials, if someone broke the law then that was a personal act, not a political one, and they were common criminals. By now, the condition of another hunger striker, Jatindra Nath Das, lodged in the same jail, had deteriorated considerably. The Jail committee recommended his unconditional release, but the government rejected the suggestion and offered to release him on bail. On 13 September 1929, Das died after a 63-day hunger strike. Almost all the nationalist leaders in the country paid tribute to Das' death. Mohammad Alam and Gopi Chand Bhargava resigned from the Punjab Legislative Council in protest, and Nehru moved a successful adjournment motion in the Central Assembly as a censure against the "inhumane treatment" of the Lahore prisoners. Singh finally heeded a resolution of the Congress party, and a request by his father, ending his hunger strike on 5 October 1929 after 116 days. During this period, Singh's popularity among common Indians extended beyond Punjab. Singh's attention now turned to his trial, where he was to face a Crown prosecution team comprising C. H. Carden-Noad, Kalandar Ali Khan, Jai Gopal Lal, and the prosecuting inspector, Bakshi Dina Nath. The defence was composed of eight lawyers. Prem Dutt Verma, the youngest amongst the 27 accused, threw his slipper at Gopal when he turned and became a prosecution witness in court. As a result, the magistrate ordered that all the accused should be handcuffed. Singh and others refused to be handcuffed and were subjected to brutal beating. The revolutionaries refused to attend the court and Singh wrote a letter to the magistrate citing various reasons for their refusal. The magistrate ordered the trial to proceed without the accused or members of the HSRA. This was a setback for Singh as he could no longer use the trial as a forum to publicise his views.0 Comments 0 Shares 0 Reviews -

Arrest of associates:

In 1929, the HSRA had set up bomb factories in Lahore and Saharanpur. On 15 April 1929, the Lahore bomb factory was discovered by the police, leading to the arrest of other members of HSRA, including Sukhdev, Kishori Lal, and Jai Gopal. Not long after this, the Saharanpur factory was also raided and some of the conspirators became informants. With the new information available, the police were able to connect the three strands of the Saunders murder, Assembly bombing, and bomb manufacture. Singh, Sukhdev, Rajguru, and 21 others were charged with the Saunders murder.Arrest of associates: In 1929, the HSRA had set up bomb factories in Lahore and Saharanpur. On 15 April 1929, the Lahore bomb factory was discovered by the police, leading to the arrest of other members of HSRA, including Sukhdev, Kishori Lal, and Jai Gopal. Not long after this, the Saharanpur factory was also raided and some of the conspirators became informants. With the new information available, the police were able to connect the three strands of the Saunders murder, Assembly bombing, and bomb manufacture. Singh, Sukhdev, Rajguru, and 21 others were charged with the Saunders murder.0 Comments 0 Shares 0 Reviews -

Assembly case trial:

According to Neeti Nair, associate professor of history, "public criticism of this terrorist action was unequivocal." Gandhi, once again, issued strong words of disapproval of their deed. Nonetheless, the jailed Bhagat was reported to be elated, and referred to the subsequent legal proceedings as a "drama". Singh and Dutt eventually responded to the criticism by writing the Assembly Bomb Statement:

We hold human life sacred beyond words. We are neither perpetrators of dastardly outrages ... nor are we 'lunatics' as the Tribune of Lahore and some others would have it believed ... Force when aggressively applied is 'violence' and is, therefore, morally unjustifiable, but when it is used in the furtherance of a legitimate cause, it has its moral justification.

The trial began in the first week of June, following a preliminary hearing in May. On 12 June, both men were sentenced to life imprisonment for: "causing explosions of a nature likely to endanger life, unlawfully and maliciously." Dutt had been defended by Asaf Ali, while Singh defended himself.Doubts have been raised about the accuracy of testimony offered at the trial. One key discrepancy concerns the automatic pistol that Singh had been carrying when he was arrested. Some witnesses said that he had fired two or three shots while the police sergeant who arrested him testified that the *** was pointed downward when he took it from him and that Singh "was playing with it." According to an article in the India Law Journal, the prosecution witnesses were coached, their accounts were incorrect, and Singh had turned over the pistol himself. Singh was given a life sentence.Assembly case trial: According to Neeti Nair, associate professor of history, "public criticism of this terrorist action was unequivocal." Gandhi, once again, issued strong words of disapproval of their deed. Nonetheless, the jailed Bhagat was reported to be elated, and referred to the subsequent legal proceedings as a "drama". Singh and Dutt eventually responded to the criticism by writing the Assembly Bomb Statement: We hold human life sacred beyond words. We are neither perpetrators of dastardly outrages ... nor are we 'lunatics' as the Tribune of Lahore and some others would have it believed ... Force when aggressively applied is 'violence' and is, therefore, morally unjustifiable, but when it is used in the furtherance of a legitimate cause, it has its moral justification. The trial began in the first week of June, following a preliminary hearing in May. On 12 June, both men were sentenced to life imprisonment for: "causing explosions of a nature likely to endanger life, unlawfully and maliciously." Dutt had been defended by Asaf Ali, while Singh defended himself.Doubts have been raised about the accuracy of testimony offered at the trial. One key discrepancy concerns the automatic pistol that Singh had been carrying when he was arrested. Some witnesses said that he had fired two or three shots while the police sergeant who arrested him testified that the gun was pointed downward when he took it from him and that Singh "was playing with it." According to an article in the India Law Journal, the prosecution witnesses were coached, their accounts were incorrect, and Singh had turned over the pistol himself. Singh was given a life sentence.0 Comments 0 Shares 0 Reviews -

Delhi Assembly bombing and arrest:

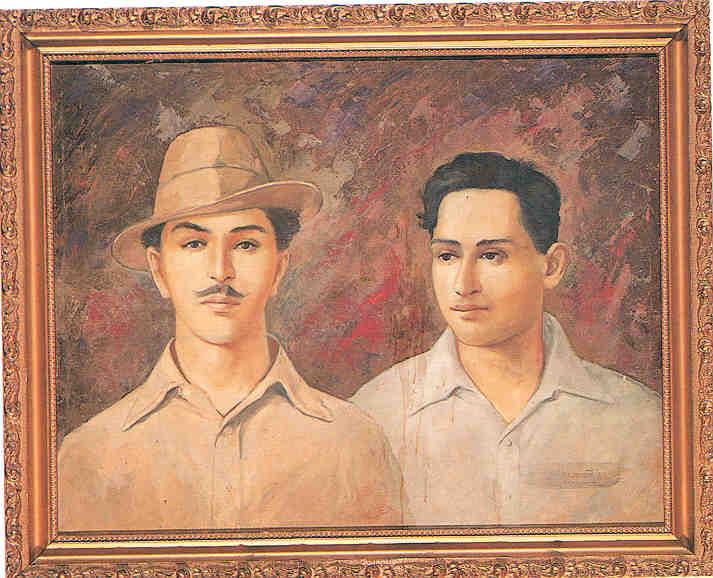

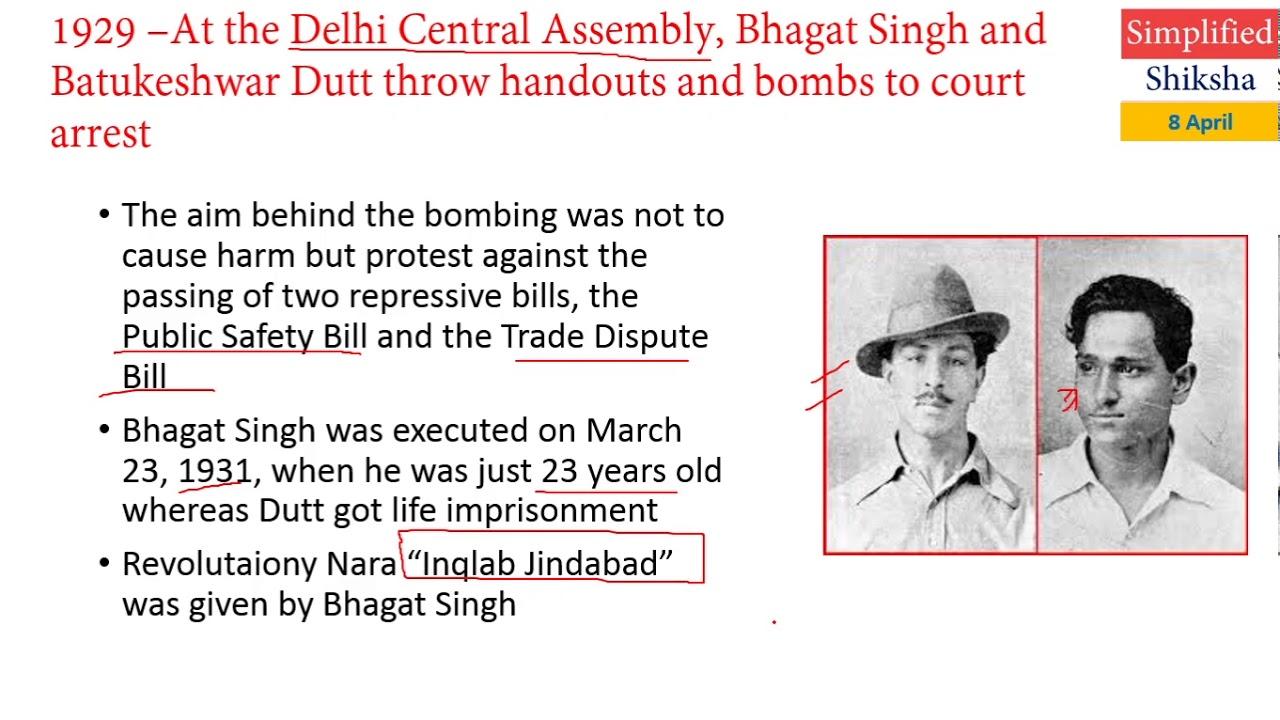

For some time, Bhagat Singh had been exploiting the power of drama as a means to inspire the revolt against the British, purchasing a magic lantern to show slides that enlivened his talks about revolutionaries such as Ram Prasad Bismil who had died as a result of the Kakori conspiracy. In 1929, he proposed a dramatic act to the HSRA intended to gain massive publicity for their aims. Influenced by Auguste Vaillant, a French anarchist who had bombed the Chamber of Deputies in Paris, Singh's plan was to explode a bomb inside the Central Legislative Assembly. The nominal intention was to protest against the Public Safety Bill, and the Trade Dispute Act, which had been rejected by the Assembly but were being enacted by the Viceroy using his special powers; the actual intention was for the perpetrators to allow themselves to be arrested so that they could use court appearances as a stage to publicise their cause.

The HSRA leadership was initially opposed to Bhagat's participation in the bombing because they were certain that his prior involvement in the Saunders shooting meant that his arrest would ultimately result in his execution. However, they eventually decided that he was their most suitable candidate. On 8 April 1929, Singh, accompanied by Batukeshwar Dutt, threw two bombs into the Assembly chamber from its public gallery while it was in session. The bombs had been designed not to kill, but some members, including George Ernest Schuster, the finance member of the Viceroy's Executive Council, were injured. The smoke from the bombs filled the Assembly so that Singh and Dutt could probably have escaped in the confusion had they wished. Instead, they stayed shouting the slogan "Inquilab Zindabad!" ("Long Live the Revolution") and threw leaflets. The two men were arrested and subsequently moved through a series of jails in Delhi.Delhi Assembly bombing and arrest: For some time, Bhagat Singh had been exploiting the power of drama as a means to inspire the revolt against the British, purchasing a magic lantern to show slides that enlivened his talks about revolutionaries such as Ram Prasad Bismil who had died as a result of the Kakori conspiracy. In 1929, he proposed a dramatic act to the HSRA intended to gain massive publicity for their aims. Influenced by Auguste Vaillant, a French anarchist who had bombed the Chamber of Deputies in Paris, Singh's plan was to explode a bomb inside the Central Legislative Assembly. The nominal intention was to protest against the Public Safety Bill, and the Trade Dispute Act, which had been rejected by the Assembly but were being enacted by the Viceroy using his special powers; the actual intention was for the perpetrators to allow themselves to be arrested so that they could use court appearances as a stage to publicise their cause. The HSRA leadership was initially opposed to Bhagat's participation in the bombing because they were certain that his prior involvement in the Saunders shooting meant that his arrest would ultimately result in his execution. However, they eventually decided that he was their most suitable candidate. On 8 April 1929, Singh, accompanied by Batukeshwar Dutt, threw two bombs into the Assembly chamber from its public gallery while it was in session. The bombs had been designed not to kill, but some members, including George Ernest Schuster, the finance member of the Viceroy's Executive Council, were injured. The smoke from the bombs filled the Assembly so that Singh and Dutt could probably have escaped in the confusion had they wished. Instead, they stayed shouting the slogan "Inquilab Zindabad!" ("Long Live the Revolution") and threw leaflets. The two men were arrested and subsequently moved through a series of jails in Delhi.0 Comments 0 Shares 0 Reviews

More Stories